Few women in twentieth-century Britain are as instantly recognisable — or as reductively remembered — as Christine Keeler. Her life was defined by the Profumo Affair of 1963, a political scandal that brought down the Minister of War, John Profumo, and exposed the double standards of a society steeped in Cold War paranoia, class prejudice, and entrenched misogyny.

For decades, Keeler’s image was reduced to a single photograph: Lewis Morley’s 1963 portrait of her nude on an Arne Jacobsen chair. Reproduced endlessly, it turned her into shorthand for scandal and desire. What disappeared was Christine herself: a young woman from a working-class background, drawn into circles of power, and punished for it more harshly than many of the men involved.

Between 2014 and 2023, artist Fionn Wilson created a cycle of six paintings that confront this legacy. Together, they form a feminist counter-archive, shifting the narrative away from scandal to complexity, dignity, and cultural resonance. Five of these paintings are already in public collections across Britain; the sixth, Christine 1963, awaits placement. Seen together, they chart a new way of remembering Keeler: not as myth or scapegoat, but as a woman whose story exposes how culture constructs, consumes, and discards its icons.

Christine and the Poisoned Apple (Hillingdon Museum and Archives)

This allegorical painting casts Keeler as Eve, bearing the apple — the oldest symbol of temptation and transgression. By invoking this archetype, Wilson makes visible the way Christine was turned into the embodiment of sin, carrying the burden of a scandal orchestrated by men but blamed on her alone.

Her gaze is not confrontational but downcast. This detail is crucial: it reflects how Christine was made to internalise the judgments of a hostile culture, forced to carry not only public condemnation but also the corrosive weight of humiliation. In her lowered eyes we glimpse how shame was imposed upon her, becoming part of her identity in the public imagination.

The apple is thus double-edged: both an emblem of the myth forced onto her and a reminder of how narratives of female “temptation” continue to punish women disproportionately.

Christine with Her Cat (Priseman Seabrook Collection of 20th Century British Painting)

If Poisoned Apple is grand allegory, Christine with Her Cat is its counterpoint: a work of intimacy and quietude. Here, Keeler is depicted in a domestic setting, in the company of her cat. The simplicity is radical — for once, Christine is not in court, not in newspapers, not in scandal, but at home.

This work humanises her. It reminds us she was not only an icon of the 1960s but a woman with an inner life. By refusing spectacle, Wilson reclaims dignity for Christine. The painting is tender without being sentimental, understated yet powerful, and it insists on a dimension of her life history that has been almost entirely erased from the public imagination.

Christine Mesmerises (Swindon Museum and Art Gallery)

This work is a conceptual pivot in the cycle. Its bold, Pop-inflected palette speaks to the language of mass media and advertising, the visual economy through which Keeler’s image circulated. Yet the title shifts the frame entirely: Christine mesmerises. She is not the mesmerised subject, not the object of scrutiny — she is the one who holds us.

In that reversal lies the conceptual brilliance of the piece. It acknowledges Christine’s transformation into cultural icon while refusing to see her only as victim. Instead, it recognises her enduring aura — her ability, even decades later, to captivate and unsettle. Wilson asks not only who Christine was, but why we continue to be mesmerised by her. In doing so, she turns the painting into a mirror: it reflects less on Keeler herself than on the culture that cannot let her go.

Christine at the Flamingo Club (Museum of London, on permanent display upon reopening in 2026)

Here Wilson situates Christine in Soho nightlife, the glamorous yet precarious world she inhabited in early 1960s London. She holds the Denning Report — the official government account of the Profumo Affair — as if it were a prop or burden. By placing it in her hand, Wilson entwines glamour and politics, showing how Keeler’s life was caught at their intersection. She surveys the report with amused disdain.

The painting acknowledges that Christine was both insider and outsider: present in the worlds of music, nightlife, and power, yet always subject to judgment and exclusion. That it will hang in the Museum of London on permanent display is significant. It embeds Keeler not only in the story of scandal but in the wider cultural history of the city — a reclamation of her place in London’s narrative.

Christine and Stephen (De Montfort University, Leicester)

This double portrait remembers Christine alongside Stephen Ward, the society osteopath whose life was also destroyed by the Affair. Ward became another scapegoat, hounded to his death by the establishment’s need for someone to blame.

By painting them together, Wilson creates an elegy. The work resists sensationalism; it is subdued, reflective, almost mournful. It positions Christine and Stephen not as headline-makers but as casualties of a ruthless public narrative. This painting extends the series from portraiture into memorial, underscoring the human cost of political scandal.

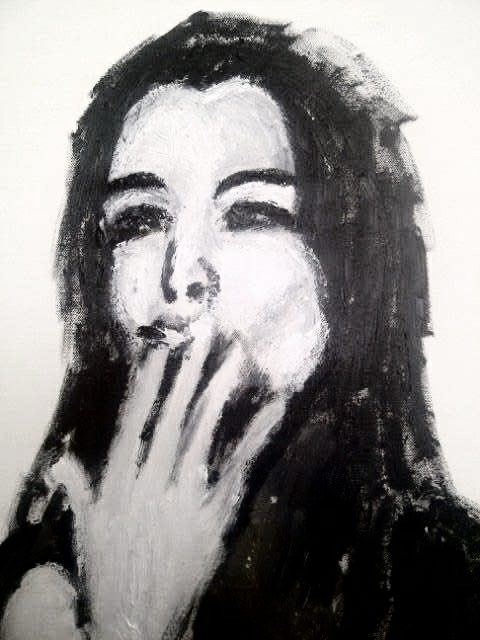

Christine 1963 (unplaced)

Painted in stark monochrome, Christine 1963 is raw, candid, and immediate. Keeler is shown mid-gesture, cigarette raised, caught in a fleeting moment. Unlike the allegorical grandeur of Poisoned Apple or the intimacy of With Her Cat, this painting has the immediacy of a snapshot — but one transformed by paint into something rougher, more vulnerable, more real.

Smoking was a gesture synonymous with glamour, rebellion, and allure in 1960s youth culture. Yet here it is stripped of polish. Wilson captures not the posed icon but the living woman, performing herself, inhabiting the myth even as it consumes her. The work reveals Christine as neither victim nor siren but as a person — poised between toughness and fragility. It completes the cycle by providing the immediacy that the other works, bound to symbol, context, or memory, cannot.

A Counter-Archive

What binds these six paintings together is their refusal to let Christine Keeler be reduced. Each work takes on a different register: allegory, intimacy, aura, context, elegy, immediacy. Together they form a narrative arc that is both deeply personal and profoundly cultural.

Placed across multiple public collections, the series ensures that Christine Keeler’s story survives not only as scandal but as cultural history, reframed and reclaimed. It is the first sustained artistic response to her in British painting, and it offers a rare act of cultural correction: to see Christine not as history framed her, but as a woman of complexity, contradiction and dignity.

#painting #portraiture #christinekeeler #profumoaffair

Leave a comment