Within this Space

In the winter of 1882–1883 the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote an enigmatic note in a private journal that has always fascinated me. “With firm shoulders,” it said, “space stands braced in opposition to nothingness. Where space is, there is being.”

For a painter, certainly, this makes sense. When doing a painting there is no such thing as an empty space, only differences in colours and light to be manipulated. Physicists now say that physically, so-called empty space has an amount of energy that can be calculated, and it’s 0.0000000001 joules per cubic metre. And so it’s not actually empty. I’m not confident, tho, that measurable energy is what Nietzsche meant by “being”, and also, I don’t think he was referring to outer space. I think he was talking about us humans in the sense that we are the products of space.

Usually people talk about us being the products of history, our own personal history as well as History spelled with a capital H. However, for Nietzsche, allowing oneself to be, or rather to become, a product of history, would be weakness. It would, using his famous expression, be resentment. The noble person, the singular person, is a product of space, not time. He or she dominates his or her space, his or her house, the domus, which is the origin of the term “domination”. He or she was born to do so and so in a sense borne from it, and he or she is one with it.

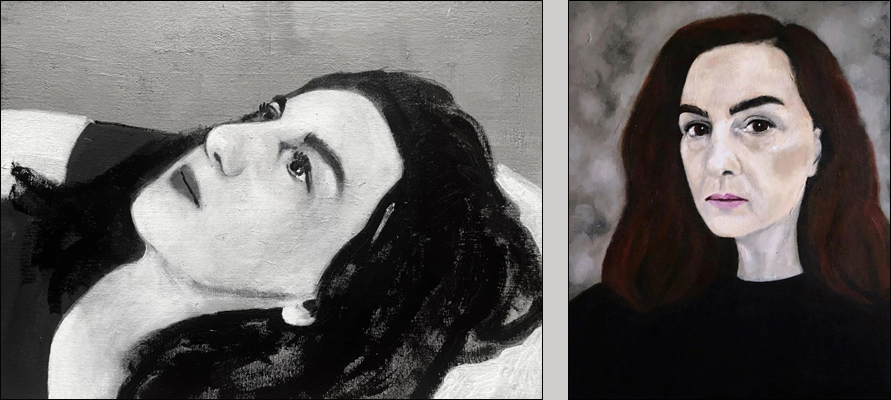

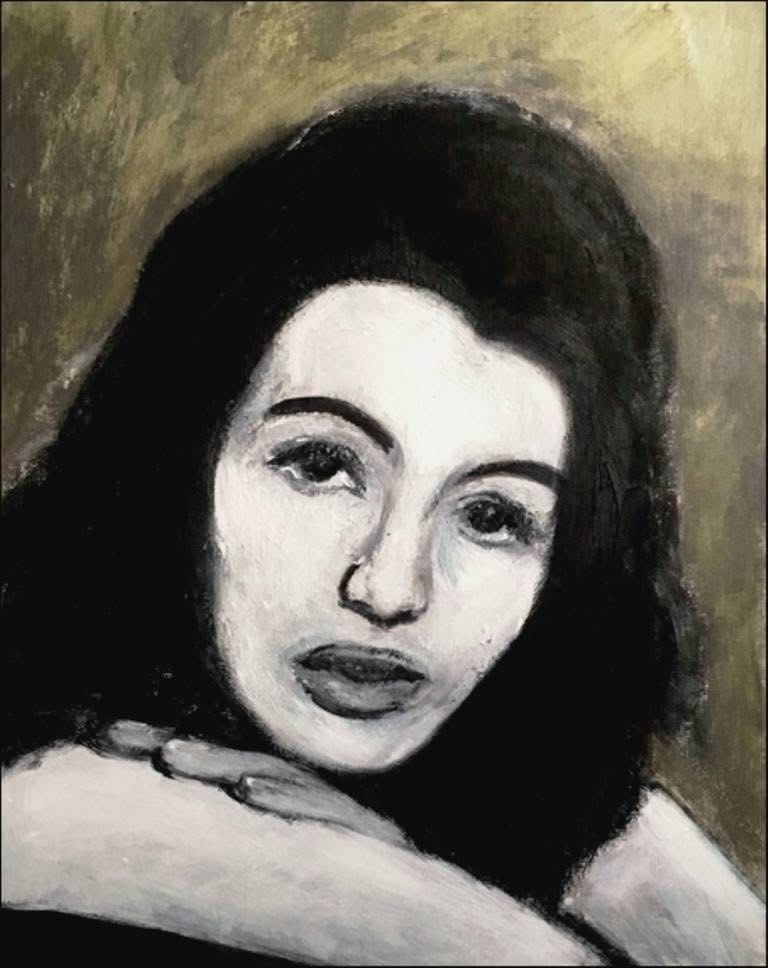

Quite obviously, very few people live like that, nor would anyone but psychopaths want to. Nietzsche wasn’t a genius because he was right but because he was wrong in spectacularly clever ways. Painters assert themselves by dominating the canvas, but otherwise they’re just as exiled in space as the rest of us. We might have been born from space, but if so, we were born as outcasts. This is what one sees in Fionn Wilson’s two self portraits: it’s the artist having captured herself in a space she can control, the space of the canvas, but as a person in a space which she can’t. This is what makes them emotionally captivating. In the one (Self portrait, summer (2024)) she is seen staring into the exact nothingness that space, according to Nietzsche, stands braced against, and in the other she is looking straight at us. When seen together, the implicit suggestion that we, as viewers, might also constitute some kind of void is unnerving. Self portrait (2021) is a particularly brilliant, psychological self portrait, done in a slightly naive, naturalistic fashion bordering on expressionism. Personally, I think it’s the best painting Fionn Wilson has done so far. The background against which she is seen is blurry or foggy. We do not know where she is, and from the look in her eyes, most likely she doesn’t know herself either. Whatever space this is, she’s not dominating it. Rather, she is lost in it. I find the tension between this sense of lostness and Wilson’s ability to control the canvas artistically very moving.

Self portrait, summer (2024) and Self portrait, post psychosis (2021)

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2024

Writer, artist and art critic

Reflecting on two portraits of Oscar Wilde

De profundis means “from the depths”. The expression comes from the Latin translation of one of the Penitential psalms, Psalm 130, that begins with the words “De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine”, “From the depths, I have cried out to you, O Lord”. “De Profundis” is also the title of a rather long letter by Oscar Wilde, addressed to Lord Alfred Douglas and written between January and March 1897 whilst Wilde was imprisoned in Reading Gaol. In the letter Oscar Wilde writes about his spiritual conversion, about faith, and about his admiration for Jesus Christ with whom he had come to identify:

“I bore up against everything with some stubbornness of will and much rebellion of nature, till I had absolutely nothing left in the world but one thing. I had lost my name, my position, my happiness, my freedom, my wealth. I was a prisoner and a pauper. But I still had my children left. Suddenly they were taken away from me by the law. It was a blow so appalling that I did not know what to do, so I flung myself on my knees, and bowed my head, and wept, and said, ‘The body of a child is as the body of the Lord: I am not worthy of either’. That moment seemed to save me. I saw then that the only thing for me was to accept everything. Since then — curious as it will no doubt sound — I have been happier. It was of course my soul in its ultimate essence that I had reached. In many ways I had been its enemy, but I found it waiting for me as a friend. When one comes in contact with the soul it makes one simple as a child, as Christ said one should be.”

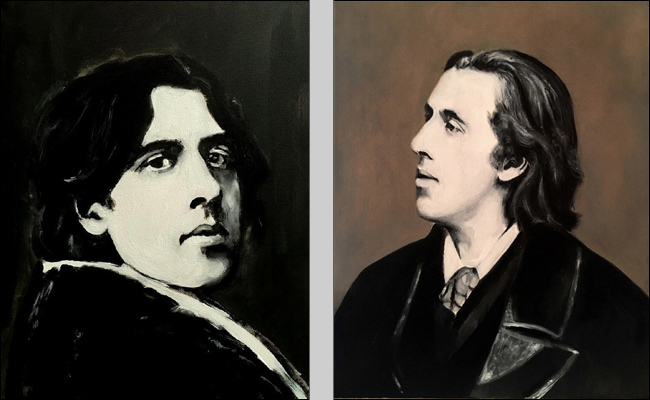

De Profundis (2016) and Oscar Wilde loves

the moon (2016)

Looking at Fionn Wilson’s portraits of Oscar Wilde, I find it difficult not just to see an Oscar Wilde longing to be freed from actual, physical confinement during his time in prison, or the Wilde of “De Profundis” about to make a spiritual u-turn. Due to the style of the paintings, the colours and what we might call their ‘air’, they also seem to me to be about history — and how history itself calls for a kind of redemption. For what are “the depths” we call from if not history, our individual as well as our collective — and what is history but that which can no longer be changed? The past is a shadowy world in which everything stands petrified, and from where only ghosts come to haunt us. As long as we can act and we have options, we can convince ourselves that we have the power to redeem ourselves through our actions. When this is no longer the case, as happened to Oscar Wilde, the present and the future turn into nothing more than extensions of the past. It all becomes history, and we can no longer save ourselves from it. When we — quoting Wilde — “have absolutely nothing left in the world”.

Art cannot redeem the past, I do not believe that — but it can do something else. It can revitalise it and bring it forth to the present in a way that creates awareness. And this — for me — is exactly what Fionn Wilson’s beautiful portraits are about. They are about not forgetting. Also, they are about interpretation. Wilson’s portraits were created inspired by photos, of course. Two arguments can be made in favour of painting from live subjects rather than photos, namely 1) that by painting from a flat photo the painter cheats her way out of the technical problem of turning a 3D vision into a 2D painting, and 2) the photo lacks the ‘vitality’ of a real life situation. But both of these are false. Solving technical problems has nothing to do with art, and vitality is just a question of sensitivity and empathy. Of which Fionn Wilson has plenty. For obvious reasons it would have been quite difficult to get Oscar Wilde to sit for a portrait, and by choosing to paint from photos Wilson has created works that not only show how art can give new life to the past, but which also and at the same time, emphasise how art itself is historical. They are paintings that deal with history — like Oscar Wilde dealt with history. I think there’s a great poetry in that.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2017

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

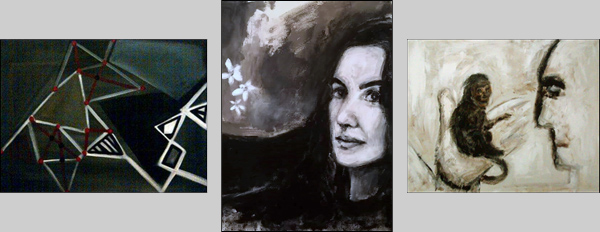

On Venus loves the moon by painter Fionn Wilson

Looking at Fionn Wilson’s Venus loves the moon, I am once again borderline annoyed that I wasn’t the one who came up with the term that so beautifully — and like a whisper, only — hints at what characterises her work, ‘spectral’. Despite its apparent simplicity, to me this particular painting sums up much of what Fionn Wilson’s painting is about. It is about dragging motifs out of the dark and giving them life as light. They often have a kind of ethereal quality to them — spectral and slightly otherworldly. This is perhaps most obvious in her landscapes and in her swan paintings. It is emphatically not that she sets out to paint anything else than what is actually there, the real; but there is something in her vision as an artist that makes her paintings stand out with this sort of Claude glass dark shine.

Fionn Wilson is brilliant at using black, and she is brilliant at darkness. It is a difficult and a delicate thing to do, to make dark motifs work, and it requires a great sensitivity. Fionn Wilson has that. Venus loves the moon is a superior example of how little you actually need in a painting, if only you know what you’re doing, and if you have the required technical skill. Both Venus and the moon have been recurring themes in Wilson’s work from her very earliest paintings: A gift under an orange moon, Lunar eclipse in the Sinai desert 2004, The flats where I live at night, and the Venus nudes, just to name some of them. In Venus loves the moon they come together like lovers in a mystery play, with the seven trees underneath as a Greek chorus witnessing the event. In Self portrait with night blooming jasmine inspired by a visit to Crete, the flowers shine like moonlight. The early painting Starman points to the fact that the cosmic element has been there all along. Stars as light out of the dark.

Venus loves the moon (2016)

Starman (2012), Self portrait with night blooming jasmine (2015) and Sphinx (2012)

Both Venus, and the moon, come to us weighed with mythology and deep meanings. Fionn Wilson has no need to elaborate on any of that, for her painting has its own depth that allows them to be and to meet in silence. It’s what it would look like, quite simply, if you went out there and looked at the sky — but also, at the same time there is nothing simple about it. The more you look at it, the more you get the feeling that there is something going on there, a secret you are being invited to learn. The painting turns into a sphinx, challenging the viewer. As with the spectral, the sphinx has been a constant element in Wilson’s work. Her portraits are questioning us, sometimes even taunting us; they show us people who are not easily explained.

To me, Venus loves the moon is almost like a meta-painting. It is a painting reflecting — as in a dark mirror — Fionn Wilson’s work up until now, poetically summing it up and taking it even further. It is an important painting in the oeuvre, and an exquisitely beautiful one.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2016

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

The Angel of Light

For a painter I can’t think of anything more daunting than creating a portrait of Marilyn Monroe. Not only did Monroe have a strikingly beautiful face, and that kind of beauty — for a painter — is a problem or a challenge in itself, but also, it is a face depicted countless times already. In fact, it is arguably one of the world’s most famous faces, on par with the ‘Mona Lisa’. How do you paint a face like that, a face that everybody knows, if not in detail then at least as a kind of symbol signifying ‘Marilyn Monroe’? This is the third thing, the third problem, and perhaps the most critical one: that Monroe by now has become larger than life, almost mythological, and as an essentially empty bit of mythology it does nothing but refer to itself, continuously and never endingly, stripping Monroe of her humanity and reducing her to a sign. She was and is, people like to say, a “sex symbol”; the important word being “symbol”. This is a major problem for an artist, for the only way to paint a symbol is to reproduce the symbol. This is what Warhol did with his Monroe series. He accepted and followed this logic. It was an artistic gesture that can’t be repeated, however, and anyone these days attempting to depict Marilyn Monroe as the symbol we can all recognise risks ending up with nothing but kitsch. The vast majority of painted portraits of Monroe fall into this category. But not Fionn Wilson’s.

Marilyn (angel of light) (2015)

The myth of Monroe is empty in the sense that it doesn’t — as a proper myth ought to do — lay a foundation for living or give us what the Greeks called a ‘logos’, an ordering wisdom or principle. In her portrait of Monroe, Fionn Wilson has managed to sort of circumnavigate all of the talk about Monroe, to skip the idea of ‘the myth of Monroe’ as a story about a now mythological person, in order to instead focus on the reason why she ended up becoming mythological in the first place. The myth might be empty, but it is full of light. That’s what makes Fionn Wilson’s portrait extraordinary and extraordinarily beautiful: that rather than showing us just a symbol, a sex symbol, it shows us both the birth of this symbol and its disintegration back into what it really is. Wilson has painted Marilyn Monroe as an angel of light, and in a way that allows Monroe the real person to come forth and breathe, without forcing her to personify any of the many ideas people have about her. Monroe ended up becoming a modern myth because of her beauty; because of the almost other-worldly light that radiated from her. Fionn Wilson’s portrait captures this in the most exquisite way.

Throughout all of her painting so far, the interplay between body and light, and the sensuality of both has been at the core of Fionn Wilson’s work. It is no wonder that she is fascinated by and drawn to the image of Monroe. The portrait of Monroe is a portrait of Monroe, but at the same time it is 100 per cent Wilson in that it, in a poetic way, sums up much of what her artistic vision is about. Monroe shines, and so does Wilson’s art. There is an angel of light in her paintings.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2015

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

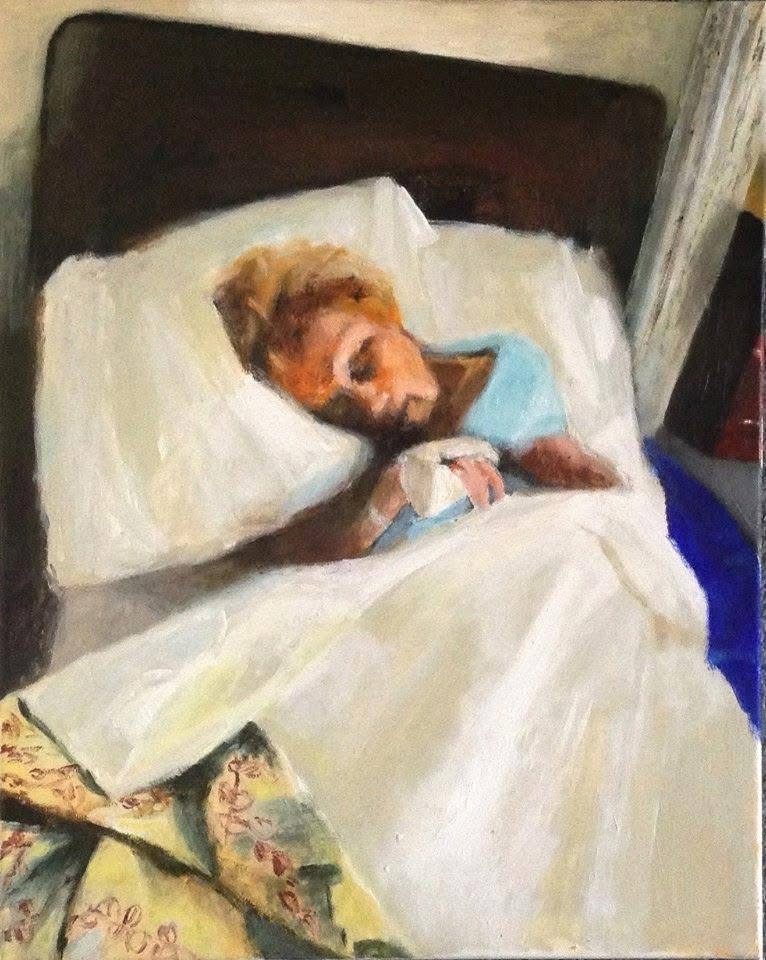

On Fionn Wilson’s portraits of Gladys

Every painting is a portrait of the artist who painted it. It can’t be helped, and this applies whether we’re talking about figurative painting, abstract, concrete or otherwise. As I have argued in another short essay on Fionn Wilson’s work, in a sense the self portrait is the most pure figurative genre, or at least the one that comes closest to the heart of the matter.

Painting a portrait of someone else, however, is an entirely different thing. Every day we are bombarded with images of people, hundreds of them, thousands of them, and we have become so accustomed to the phenomenon of the portrait that it’s easy for us to forget what an almost magical thing it is. I am reminded of a quote by Henry David Thoreau, in “Walden”, where he asks: “Could a greater thing take place than for us to look through each other’s eyes for an instant?” With everybody doing selfies these days, trying to shape a public image and control how other people perceive us, I feel that Thoreau’s question is as relevant as ever. However fascinating or amusing the selfie might be (and for an artist, of course, rewarding), the portrait of one done by another is nothing less than a small miracle. It is us seeing ourselves through somebody else’s eyes, and when the portrait is a good one, it proves and pays tribute to our deep humanity. Go look at any portrait by Rembrandt and you will see a profound understanding of, and capacity to communicate, even that about a person for which no words will suffice. It seems such a poor label to use, incapable of truly summing up all that this means, but I will nevertheless call it ’empathy’. I don’t know what else to call it. The term empathy was coined in 1909 as an attempt to translate the German expression ‘Einfühlung’, which literally means ‘in-feeling’, and this is what a good portrait is about.

Our ability to ‘in-feel’ is miraculous, but we forget. It is what makes us humans, and the good portrait shows it — but we see so many portraits, so many photos, images, again and again, that we become desensitised. And we need an artist like Fionn Wilson to remind us. It makes good sense to me that she is a big admirer of Rembrandt. Her three portraits of Gladys reveal a familiarity, an ‘in-feeling’ and insistence on what is human; a similar empathic understanding. In the midst of this rush of images that we as viewers find ourselves in (many of them quick snapshots or images intended to shock us and grab our attention) there is something persuasively and deliciously slow about Wilson’s three portraits, something distinctly un-rushed and meditative. Something silent. Gladys is a woman at the end of her life with a whole history behind her; she is right there in the paintings, and looking at them you get this sense of time stretching, the minutes turning into hours, the clock slowly ticking whilst the past moves forward to meet with the present. It is right there in the bed in Susan’s mum, Gladys. Her head resting on that pillow. It is sad, but it is beautiful, and Fionn Wilson’s portraits are full of respect and care. Again, I prefer the German word, which is ‘Sorge’. It means care or concern. In Danish we have the equivalent term ‘omsorg’, and we have the word ‘sorg’, meaning sorrow. It seems to me that this is exactly what characterises Fionn Wilson’s three portraits of Gladys, and what makes them so powerful: they show care for sorrow, and in a time of sorrow they show care.

Gladys (2015) and Portrait of Gladys (2015)

The three portraits are masterfully done, showing an incredible talent for figurative painting. Knowing that Fionn Wilson is self taught with no former training and still only a few years’ painting experience only makes it that much more impressive. Speaking as a painter myself, I have never seen anything like it. These portraits of Gladys, I believe, are amongst her strongest works — which is saying quite a bit considering the oeuvre she’s already managed to produce. They not only show her truly remarkable technical skills, but also — and vitally importantly — they prove that she is an artist with a deep interest in, and understanding of, the humane. Of the human soul or spirit. They are quite simply wonderful.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2015

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

Fionn Wilson — The Lady on Black

She came to me one morning, one lonely Sunday morning … I first discovered one of Fionn Wilson’s paintings on Facebook on a lonely Sunday morning. It was a cherry, a very lonely cherry. The cherry was thick, black, luscious, tempting, tasty — and gone: I had to buy it right off the rack, and did.

Later, when the cherry, fortunately not out of real sweet and red flesh but painted with very rich acrylics on canvas, arrived in my barn and was put up the wall, it happened to me again: Hunger. Desire. Longing.

It took some time for me, a complete no-know about art and painting, to figure out why this poor cherry attained and gained and deserved so much of my attention. The answer was: black.

If you love something really intensively, you need contrast. If you adore classical piano music (I do), you need silence, before, after and even while you are listening. If you want people to focus on one single cherry (when was the last time you did?), give it a lot of black around it.

I bought more paintings of Ms. Fionn Wilson. Unfortunately, she ran out of cherries.

But: The three of the places meaningful to my life were Paris, London and NYC. (FOR THOSE OF YOU WHO DO NOT KNOW: TODAY IT IS RYSUM.) The good news: Fionn painted all three of them: Pont Neuf, St. Pauls and Brooklyn Bridge.

I now am the happy owner of a very special memory board, and I am a collector of paintings by Fionn Wilson.

After I completed my collection, I looked at it from time to time (it is not all about shopping, only), wondering why they caught my eye to that extent. The answer, again, is: black. How much light can be thrown on objects special to us, how much focus can be drawn to our attention if we have a strong commitment to black.

Kathrin Haarstick, 2014

Director of Weltklassik

The Light Weight Secret of Bodies

There’s a kind of dialectic to much of British painting. On the one hand a kind of obsession with the accurate representation of the visual, which compared to mainland European painting seems retrograde and somewhat old fashioned. On the other hand there is a preoccupation with mass. With the weight of it all.

It was Einstein who told us that E=mc2, that mass can be transformed into pure energy. To light. Which, it often seems to me, is what Fionn Wilson’s painting is all about: transforming weight into light, most often the weight of the female body. It makes her part of a long British tradition that prominently includes such painters as J.M.W. Turner, David Bomberg and Frank Auerbach. In fact, it was Bomberg who came up with the perhaps most apt expression for what this tradition is all about, “the spirit in the mass”. The light weight secret of land and of bodies.

Whereas Turner lets it explode into abstraction and Auerbach seeks to sort of entomb and preserve the light in layers of paint, Ms Wilson also wants the sex of it – which, I become more and more convinced, is the real challenge she faces in her painting: how to make the Einsteinian formula balance so that we get the light but still enough mass and weight to maintain the sensuality?

In this particular painting, I think she has managed to do just that. It’s a heavy body turned into light and the movements of light – but still, it’s a sensual body. As simple as it might seem, with its Turner colours and Picasso-like crudeness it carries a whole lot of history, including that of the Art Brut movement. However, the exact point of this kind of painting is to transcend the history of things, the history of what weighs, in order to get to the beauty of what is permanent or perhaps even infinite, the energy or the spirit.

Which is just another way of saying, of course, that it is a kind of painting driven by longing.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2013

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

On Blonde 2, by painter Fionn Wilson

The American abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning once said that ”Flesh was the reason oil paint was invented.” As a painter, at times it’s hard not to think the opposite to be true as well, that flesh was invented to be painted, especially the human flesh and the naked body. The female nude with its delicious curves and voluptuousness is particularly appealing. There is a connection, certainly a poetical and an erotic one, between the way a woman fills her skin and the way paint fills a canvas — and let there be no doubt about it, painting is a sensual process.

Like undressing and being nude usually is, painting is something very intimate that takes place within a confined, personal space. It is a trademark of Fionn Wilson’s painting in general that she never betrays this feeling of intimacy. She doesn’t put things on display, and rather than trying to accommodate or please the viewer’s voyeuristic desires, she invites him or her to dwell upon the delicacy, the tenderness and — quite often, also — the powerfulness of the intimate.

Her painting Blonde 2 which was judge and writer Jan Woolf’s favourite in the 2013 ‘The International Women’s Erotic Art Competition’, is a perfect example of this. It is an extremely sexual and very up front painting, almost obscenely so — but it isn’t. Instead, Fionn Wilson has turned the painting into a powerful and refined meditation on female lust, not as something objectified , dissected or studied, but — and I will deliberately put it like this — like a curving of the private, intimate space.

For, it seems to me, Fionn Wilson’s nudes are not just paintings of curved, naked bodies. They are also, importantly, paintings of curved spaces — or perhaps more accurately: the spaces that the paintings make and invite the viewers into, are curved ones. Looking at a Wilson painting you find yourself drawn into a kind of circle, emotionally gravitating towards the centre. This is far from always true with paintings. Many expressionist artists’ works seem eager to (in a manner of speaking) sort of reach out into public space and be everywhere at once, and it is only through their reaching — when successfully done — that they gain some kind of gravitational force themselves. A Fionn Wilson painting is something quite different. It has a strong, emotional core that allows it to generate a space of its own, not apart from the public one, but as intimacy. Right there.

With Blonde 2 (as with the rest of her nudes) Fionn Wilson has achieved something which hardly any contemporary painters even bother to attempt: to give us a strong and convincing impression of female sexuality. Not a prettified one, not an obscene one, and not as an illustration of some more or less clever gender political point. But for real. Full of respect for the person painted and with amazing talent. It is a brilliant painting.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2013

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

On a portrait of Christine Keeler by painter Fionn Wilson

In Britain, Christine Keeler is an icon. It’s been decades since the Profumo Affair, but ever since, the youthful face of Christine Keeler as she looked back then, has been synonymous with political scandal and intrigue. Keeler herself has had to pay dearly for it, her public image being frozen in time like that, and she has spent the last many years just trying to be left alone, avoiding the press. She’s lived and she’s aged, but the face of Christine Keeler that became part of British culture, perhaps most famously through the black and white photos taken by Lewis Morley, remains the same. And how do you paint such a face? How do you paint a face that’s been hijacked by the public, turned into a sign, and which comes with so much talk and so many agendas, so much history — in order to get to something personal and authentic?

The answer, actually, is an easy one. There is only one thing that will cut through the — quoting the Danish expressionist painter Jens Søndergaard — “nonsense of the outside world” and let things breathe anew, and that is love. And Fionn Wilson loves Christine Keeler. It’s obvious from her portraits. The Christine Keeler portrait below doesn’t show us a political figure or an icon, but a vulnerable and real woman with a slightly wounded look. She’s not really looking out, she’s looking in, caught in a moment of self-reflection. In that sense, it can be said to be a mirror image. A painting about reflection.

Fionn Wilson’s painting, especially with reference to her early work, is spectral. Her work encompasses a variety of subjects, including portraits, landscapes and still life, but what most of her paintings share is a certain quality, as if she had dragged them out of a Claude glass. As if they were light. She paints with light, like light in a mirror, and spectral painting seems a very apt term for it. But also, as in this particular portrait of Christine Keeler, many of Wilson’s paintings deal with the emotional spectres that haunt us and feelings of loss, abandonment and isolation — and the upsurge of a life force, sexuality, which she also paints as a kind of light breaking through and taking shape, usually the shape of a woman.

In many ways Christine Keeler is the perfect motif for Fionn Wilson. Even before the Profumo Affair, Keeler had experienced more than a fair share of hardship, and since the scandal she has become isolated, forced to live with her ghosts. She was just a young woman when John Profumo was forced to resign, and she was hurt. At the same time, however, Keeler was also a powerful and somewhat rebellious figure, sexual and with an attitude. It is almost like Christine Keeler has herself become a prism for Fionn Wilson, showing us all the levels on which she meditates on light and reflection in her painting. In one portrait we see one side of Keeler, in another we see a different side — and when seen together, they strangely mirror each other. What appears is a faceted image of a real woman, not a cultural icon, or just a victim, or just a sex symbol, but a person. Which is what love does, it lets the person come forth.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2016

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen

On Fionn Wilson’s self portraits

Two things happened recently, which both made me think of Fionn Wilson’s work. I went to see a J.M.W. Turner exhibition, and as I was looking at all those big, bright canvases it occurred to me that there was a kind of reverse relationship between these and Fionn Wilson’s paintings. Whereas Turner’s paintings all look like something dragged out from a clear and blinding light, Wilson’s look like they were painted forth from a dark and mysterious mirror. The other thing was an interview with Frank Auerbach in The Guardian with Auerbach talking about John Constable. ”I am struck by” he said, ”that sense of how Constable has gone round and round and round the subject. […] Everything has been worked for and made personal so you sometimes feel that Constable’s own body is somehow inside the landscapes there.” This made me think of Fionn Wilson’s self portraits.

If you’re an artist, a real artist, painting is exploration. People seem to have a tendency to think that painters are out to express something (and then they become suspicious when the painters can’t quite explain what it is). No. People working in advertising are out to express something, and politicians and people who want you to donate to their church. What a painter does is exploring and investigating his or her given reality in order to understand it, perhaps in order to come to terms with it or be reconciled with it, and he or she does this using paint and brushes. That is all. And by doing so, by going deep and ”round and round the subject”, the painter helps open up reality for the rest of us, and helps keeping it open. Referring to Max Beckman who once said that ”I hardly need to abstract things for each object is unreal enough already, so unreal that I can only make it real by means of painting”: painting — like all art — is reality maintenance.

No given reality is more obviously and unavoidably there than our own physical presence, our bodies and our faces. In some ways, it could be argued, the self portrait is (with a word Fionn Wilson would most probably dislike) the most pure figurative genre. Unless you’re trying to simply make yourself look as handsome or attractive as possible, in which case you’re not an artist, doing a self portrait is exactly what painting is all about, exploring and investigating what is there — and with no other agendas. There is no ‘point’ to doing a self portrait except to go ”round” your most intimate and personal reality, trying to understand it. Essentially, there is no difference between painting a self portrait or a landscape, but with the self portrait you’re closer to the heart of it all, where it all comes from.

This is clear when you look at Fionn Wilson’s oeuvre so far. She’s done quite a few self portraits, several of which ranging among her strongest works, and she’s done them in various styles. There are naturalistic self portraits, and impressionistic and expressionistic portraits. Self portrait whilst listening to the rain is a powerful expressionistic work with bold and clear lines and a glowing combination of colours. Compare this to Self portrait, winter, another expressionistic work, but this one more questioning and reminiscent of Munch. Auerbach’s remark about Constable going ”round and round and round the subject” reminded me of Wilson, because in her self portraits this is exactly what she does. Fionn Wilson also does landscapes and cityscapes and other kinds of paintings, but with intervals she will return to the self portrait. Seen from afar, it’s like she periodically will retreat back to what is most private and most emphatically present for her in order to focus on that — and to use it to vitalise her painting and keep it true and honest. There is a great beauty to this, I think. Trying to understand and capture the most basic, her own physical presence — and not some abstract idea, not a concept, not a theory — she engages with painting at the most fundamental and all-important level, and the impressive artistic quality of her self portraits bears witness to the fact that it kindles her art.

What is doing a self portrait? It’s an encounter with yourself through the medium of painting, perhaps — as Beckmann said — in order to ”make it real”. But it is also and vitally the other way around: it is engaging with painting using yourself as the medium, which is what painters always do, obviously, but focused and cut to the bone. It is a kind of ground work. Looking at Fionn Wilson’s self portraits, I get the distinct impression that this is how it works for her. With intervals she will return to the ground, to re-examine and re-evaluate, but also to get grounding. Which, I believe, is the hallmark of a real painter, a real artist, that there is such a ground. Not a stable one, but a fertile one with a root problem that will feed the artist and give reasons to go on, to go ”round and round and round the subject”, painting, re-painting, trying again, trying in a different way. And Fionn Wilson is a real painter. A real artist, committed to getting it right.

Bo Gorzelak Pedersen, 2015

Art critic for the Danish art paper Kunstavisen